Stage Monitoring: Some Do’s and Don’ts

Published on Friday 19 August 2022

Great stage sound is essential if you want to put on a great live performance but can be difficult to achieve. Luckily, the tools that can help have already been invented: floor monitors and in-ear monitors. That said, these bits of kit also cause the occasional issue. In practice, balance and discipline are what makes or breaks great live sound – monitoring actually only comes in third place.

- The Aim: No Monitoring

- Problem-Stacking

- Discipline and Egos

- Holding Vocal Melody Lines

- Feeling Closed Off

- Find the Cause

- Bobbins and Ashtrays

- Musical Information

- The Monitor Tech

- Worth Knowing

- A Tip for Keys Players

- A Special Monitoring System

- See Also

The Aim: No Monitoring

“On stage, the idea should be to play without any monitoring,” says Ampco project manager, Nico Raatgever. “If a band has their on-stage balance properly dialled, there’s little, if any monitoring needed. That would be the ideal situation. In practice, however, you often see the opposite happening on stage, with some bands opting to set up more monitors than you swing a stick at.”

As we’ll explain in a bit, monitoring comes with pros and cons. In this article, we’ll talk about the how-and-why and offer up a handful of practical, potentially gig-saving solutions. The consulted expert for this piece is Nico Raatgever, who’s currently working as a project manager at Ampco but previously spent years working as a sound engineer, taking care of the monitoring for big names in Belgium and The Netherlands like Soulwax, Raccoon, Boudewijn de Groot, and others. “Raccoon has a producer who spends a lot of time perfecting the set-up and sound balance during rehearsals. I remember a Raccoon gig in Austria where I took care of the monitoring. The venue wasn’t kitted out well so we were forced to devise and improvise all kinds of things, including the monitoring set-up. Thanks to the band’s pre-optimised on-stage balance however, none of it proved to be problematic. Bands in the top-40 circuit generally have their on-stage balance sorted, which gets easier when you play in the same line-up more often and get more experienced.

Problem-Stacking

Nico is an outspoken advocate for minimal live monitoring: “The technical argument would be that placing a bunch of monitors on stage crowds too many sound sources together. All of those projected soundwaves affect each other, which only muddies the sound. Every additional speaker diffuses the sound some more until eventually even the vocals become hard to distinguish. The more monitors you set up, the more problems you’re looking at.”

Proper stage balance ensures minimal monitoring is required, and can be achieved through the correct configuration of your instruments and amplifiers. “Seek the optimal balance without the help of any monitors,” Nico suggests. “Once you’re done, add your monitors where needed. Vocals are a prime candidate here, since it’s the softest acoustic sound of the band while, if there’s any member of the band that needs to be able to hear what they’re doing, it’s the singer.”

Discipline and Egos

Aside from how the instruments and amps are set up, discipline is another thing that’ll determine your stage balance. “In practice, you quite often see one or several musicians ‘carrying’ the rest of the band,” Nico says. “One of them will then turn up their amp before the next one does because they’re no longer able to hear themselves play. Before you know it, you’re playing at twice the volume that you started with, which won’t necessarily make things any better.”

A lack of discipline and massive egos don’t do the balance any good. “You see it sometimes at big rock shows, where musicians have a certain tendency to want to prove themselves. Monitoring is becoming more popular among smaller rock bands while jazz combos and big bands rarely make use of any on-stage monitoring system. It’s odd in a way, but it’s to do with the way you’re ‘handling’ the music. More experienced musicians are inclined to listen to their music as a whole, whereas less experienced musicians will usually opt to zoom in mostly on their own playing, using the technology as a tool to listen mainly to themselves.

Holding Vocal Melody Lines

The drums are the starting point for your live sound, since dialling in the volume is trickier than for most other instruments. Sometimes, acrylic screens are used to wall off the drum kit and counter crosstalk (drum sounds getting picked up by microphones set up to do a different job). Then, based on the volume of the drums, the electric guitar amps can be dialled in, followed by the bass and any keyboards. “If one instrument crosses the line, the rest will follow,” says Nico. “As a result, the volume will gradually increase during the set, with the vocals forced to stay on top. At the same time, the vocals need to retain enough clarity for the vocalist to hear and feel them. Loud ambient sounds can hinder the singer’s ability to hold melody lines. Ever seen a singer put a finger in their ear? It’s what most will do when they’re struggling to identify the pitch, and it’s something that oughtn’t happen to be honest.”

There are more and more singers as well as instrumentalists performing with in-ear monitors. “These have their advantages, as well as some drawbacks,” says Nico. “The great thing about in-ear monitors is that they almost fully take ambient noise out of the equation. And, used correctly, they even provide hearing protection. On the other hand, in-ear monitoring demands discipline. Musicians that know what they’re doing will start out with the lowest setting and tweak their way up until they’re just able to hear what they need to hear. The opposite quite often happens when tapeshow-artists (singers backed by their own orchestra) perform: they tend to turn their in-ears up so far that the risk of hearing damage is real, in which case what should be serving as hearing protection, is actually hurting your ears.” For more info on in-ear monitoring, check out our blog: In-Ear Monitors: For Live and Rehearsal Use?

Feeling Closed Off

For sound techs, in-ear monitoring means there’s much less ‘noise’ to deal with. “If certain artists were to shut down their PA system mid-gig, it would be almost silent on stage,” Nico illustrates. “The advantage for the sound tech is a cleaner ‘room’ mix at a more controlled level.” In-ear monitoring means listening to a near CD-quality mix, which comes with a perk as well as a drawback. The most frequently heard complaint when it comes to in-ear monitoring has to do with feeling closed off, so while it provides high-definition sound, it lacks that ‘live’ feel. To give musicians an easier time connecting with the crowd, some sound techs will set up microphones on stage aimed at capturing the ambiance and the sound of the crowd, which is then mixed in with the monitor mix. Sidefills are also used, which are monitors placed on the sides of the stage to literally feed in sound from the side to enhance the monitor mix and, again, improve that ‘live’ feel. “But those mainly serve as band-aids,” Nico remarks. Also, there’s another special in-ear monitoring system from Aviom that deserves a special mention, so more on that later.

Find the Cause

Back to stage balance, where Nico’s advice is to check your balance before you tweak your monitor set-up. “If the balance is off, find the cause before you touch any knobs. If it’s the guitar that’s too loud, turn it down. If the guitarist refuses, chances are they either have an ego-problem or they’ve got a valve amplifier that only sounds right after it passes a certain volume threshold. The latter is a bad excuse since there are plenty of tools you can use these days to distort your amp at lower volumes.” Just like so many guitarists, drummers also love to be loud. “The hi-hat in particular can be extremely piercing and ring out on top of everything else. It’s something drummers need to pay attention to, and the same goes for the drumheads they use. Ideally, drummers configure their kits based on the circumstances per gig – their cymbals as well,” Nico suggests.

In a traditional setup, the bassist and guitarist are on opposite sides of the drummer, who often sits on top of a platform called a drum riser, giving them a better view of the audience and vice versa. That said, drum risers place the cymbals at the singer’s ear height which can be bothersome, so you’ll want to use an acoustic screen. The same goes for any wind instruments, which can be monitored using special soundback acoustic monitors to gain two advantages: one, the wind section will be able to clearly hear the sound they’re making, and two, it’s more comfortable for any musicians in front of them.

Bobbins and Ashtrays

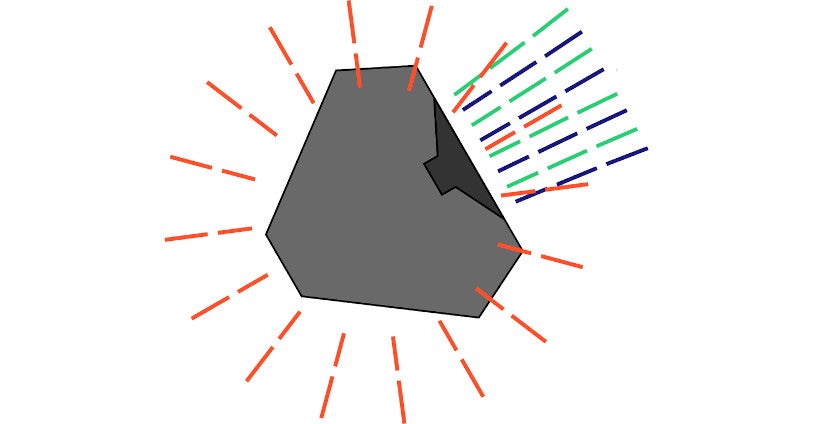

That covers it for stage balance. Imagine a gig where you’re playing over a PA system and a set of stage monitors. Now, let’s look at it from a musician’s perspective before we take a sound tech’s point of view. “What’s important to know for musicians is that anything you don’t put in, can never come out either,” says Nico. He clarifies: “It starts with the musician. You have to realise that singing softly has consequences for the sound that comes out of your monitors. You can’t keep turning that up in terms of volume because you’re bound to bump into feedback sooner or later. I see PA and monitor systems as a kind of magnifying glass: you can enlarge something, but not infinitely. That also applies to sound. If there are no lows in your bass, you can tweak your EQ for days but nothing will ever happen.” The same goes for the quality of your sound: bad stage sound simply can’t be turned into great stage sound. This has consequences for monitoring, but it’s also important to realise that middle and high frequencies are directionally sensitive while lows aren’t. Sounds below 100Hz will travel in all directions, while mids and highs are shot out of speakers in a straight line and will continue to follow that trajectory (as illustrated below). As such, it’s essential to optimally aim the sound projection of your monitors. If they’re tilted slightly too high or too low, this can easily throw the sound off course, which is when a bobbin, an ashtray or any other small object can come in handy to help you tweak the tilting angle of the monitors. Remember that singers need to be able to clearly hear the mids and highs, which are exactly the frequencies that are most likely to be thrown off course. While vocals are of course also made up of lows, these frequencies aren’t directionally sensitive and, besides that, sounds below 80Hz don’t contain any essential bits of music.

Frequencies below the 100 Hertz mark travel in all directions while the mids and highs are shot out in a straight line and will continue to follow that trajectory.=

Musical Information

Let’s return to ‘musical information’ for a second. In live situations, sound frequently gets filtered, meaning certain frequency ranges are cut or boosted with an equaliser to either compensate for the acoustics of the room or, more commonly, to counter feedback. Depending on the layout of the room, some frequencies may be extra-susceptible to feedback and will need to be reined in accordingly. “It’s a logical move, but one that doesn’t always work out well for the musicality,” Nico says.

Imagine taking some of the lows out of the bass via your equaliser. As a result, you can no longer hear the low E string properly, which will then give you the idea that the bass is too soft. Always make sure your sound is equally loud across the entire sound spectrum – if you don’t, you’re bound to miss out on bits of musical information. Equalisers can be a good tool, but incorrect use only results in a loud and poor sound.” So many monitor-based issues could be avoided if musicians and technicians would simply communicate better. But that’s often where things go wrong, Nico knows. “You often feel a sense of distrust of sound techs among musicians. To some extent, I can see where they’re coming from because, in my experience, not all sound engineers are equally humble-and-kind. If “I know what I’m doing – it’s my gear and I’m the one who decides how it’s going down” sounds familiar, then you know what I’m talking about. Then again, I have to say I’ve been seeing less and less of this attitude in recent years. Rightly so, because a sound engineer is there to provide a service for the musician and the audience. People go to gigs to see the artists, not to check out their mixing consoles.”

The Monitor Tech

Let’s assume both the musician and the sound tech have good intentions. What’s the best way to work together? “After you’ve introduced yourself and told them which instrument you play, it’s important to clearly explain what you want to hear back in your monitor sound, which may be the vocals, a little keyboard and a little guitar,” Nico says. “Dialling in the full mix is never a good idea. Limit the monitor sound to three or four things so that you only have to make slight balance adjustments when it’s time for the sound-check.” The monitor mix is usually dialled in using the front of house mixer at smaller gigs while, at bigger gigs, there’s usually a monitor tech on stage who controls the monitors via a special monitor mixer. “A monitor tech is almost like a psychologist,” Nico remarks. “A good technician can immediately tell whether a musician is having a good or a bad day. Live sound plays an important role here, since bad live sound is difficult to turn into good music. Techs also need to keep the music in mind and adapt as well as anticipate accordingly. And it’s better to anticipate than to wait until one of the musicians makes a request.” To communicate, musicians and techs also like to use predetermined signs and signals. “I know a big singer-song-writer who uses like ten different facial expressions to let their tech know that the monitor sound needs tweaking.

Worth Knowing

A Tip for Keys Players

Keyboard players often work with presets. The volumes of those presets can differ massively, which can create a kind of yoyo-effect when you’re toggling between presets, making things harder for the sound tech. To help them out a little, check how big the volume differences in your presets are and try to reduce any massive differences as much as possible by tweaking the preset parameters.

A Special Monitoring System

A special monitoring system that’s worth mentioning in closing is the Aviom Pro16 Monitor Mixing System. This unique system basically gives every musician access to their own 16-channel mixer coupled with an in-ear system where each mixer is connected to the digital main mixer via an ethernet cable. “It’s great,” Nico says. “It does require more cables and offers the sound tech less of a challenge. And the number of channels is limited to 16, which means you’re forced to create groups sometimes.” Aviom’s system is mainly used in TV studios.

See Also

» Floor Monitors

» In-Ear Monitors & Accessories

» Acoustic Screens

» All PA Gear

» What are the Best In-Ear Monitors for Me?

» In-Ear Monitors: For Live and Rehearsal Use?

» The Mixer: Functions & Connections Explained

No comments yet...